On Playing With Docker - Part 1

Oh boy, has it been a while since I’ve written anything. Well, I suppose now is a better time than any to break radio silence.

Over the last 12+ months I’ve played with Docker to varying degrees. Docker scratches something of an itch for me. It fulfills that burning desire I have to tinker with things. I enjoy setting things up, plugging things together and watching them go. This desire is likely the reason I picked up a passing interest in electronics and spend my spare time setting up VMs. Docker really scratches something of an itch for me.

For me, playing with Docker has been one of those slow-burn awakening moments. Docker represents a new way of managing applications, from development, through QA and in to production. As I read more and more about the many ways people are making use of Docker, and the more I play with it myself I am surprised by just how many day-to-day software development problems I face that I feel that Docker could help alleviate. Perhaps I’m just impressed by my shiny new hammer, but it’s quite rare that I get this excited for a piece of software.

Running Applications

Docker makes it super simple to run third-party applications. Want to run a chat server? Need a new instance of a datastore? Want to try out some service discovery technology? They’re all a docker run ... command away. For toying around with new tools and applications this is a real boon. The container’s image comes along with everything it needs to run, and while there may be some overhead in this, when you’re just toying around that’s not necessarily a big deal.

One of the first of my own projects that I experimented on with Docker was my honours project

This also goes for first-party applications too. Take the case of a frontend developer needing to hook up their application with a version of the backend that has some in-flight changes to it, it’s very simple for you to ship your changes as an image that they can simply cast docker run at and be up and running. There’s no worrying about what versions of the .NET framework they’ve got installed on their machine or whether or not their local JBoss instance is configured correctly, just docker run ... and off you go.

Development Stacks

When you’re working on an application you often rely on resources that you aren’t explicitly responsible for. Having to remember to spin up a local copy of the database and trying to keep its schema and configuration data up to date can be a consistent source of frustration. Having your application connect to shared datastores leads to different types of headaches, where what you’re connecting to is now prone to having data manipulated unexpectedly, such as having simple fields in some documents being converted to more complex structures, breaking your application.

With Docker you can make it really easy for every developer to set up their local development environment, and have all the configuration worked out for them ahead of time, all thanks to Docker Compose. Docker Compose allows you to define how multiple docker containers should be spun up and configured, and then with a simple docker-compose up you can have your dev environment set up and ready to go.

As an example of what you can do, below is a simple docker-compose.yml file that I use to play around with GitLab at home. It defines a few containers to set up, one for the application itself, and a build runner, and links them together. It also sets up the appropriate port forwarding and volume mounts for data persistence. Do note however, that I’ve already set up the correct settings for the build runner so that it will connect to the main server instance, the config for which is maintained in the attached volumes.

version: '2'

services:

gitlabserver:

image: gitlab/gitlab-ce

container_name: gitlabserver

ports:

- "80:80"

- "7080:80"

- "7022:22"

volumes:

- ~/Docker/Volumes/gitlab-server/etc/gitlab/:/etc/gitlab/

- ~/Docker/Volumes/gitlab-server/var/log/gitlab/:/var/log/gitlab/

- ~/Docker/Volumes/gitlab-server/var/opt/gitlab/:/var/opt/gitlab/

runner:

image: gitlab/gitlab-runner

container_name: gitlabrunner

volumes:

- /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock

- ~/Docker/Volumes/gitlab-runner-0:/etc/gitlab-runner

links:

- gitlabserver

You can of course combine this sort of configuration/orchestration with setups that allow for hot-reloading and debugging of code within the containers, giving you a really rapid method of setting up a new development environment.

Testing Environments

One of my pet peeves is receiving false-positives from the QA test suite because of environmental instability. If you can’t have confidence that failures in your test suite are actually failures, how much time are you potentially wasting investing bogus results? I’m yet to have a chance to give the following idea a trial by fire, so take it with a heaping spoonful of skepticism, but I’m hopeful that it’s manageable.

When you have several different types of testing (unit, integration, end-to-end) it can often be tricky to make sure all the moving pieces line up for a given feature. If your change requires a DB schema change, backend code deployed, frontend code deployed, and a specific version of the QA suite run against it how do you manage to test all these pieces other than just merging the changes in to the mainline and having it flow down the deployment pipeline?

You don’t let your code get merged in to the mainline development branch without passing your unit and integration tests (I hope), so why let it be merged if it can’t pass your other forms of testing? Why make a distinction at all? I’m hoping that with Docker there will some day soon be a way to manage such testing that isn’t extremely onerous. I’m not sure how you would get your build server to talk to your QA Software, but Docker could at least help in the deployment and infrastructural setup of the test environments.

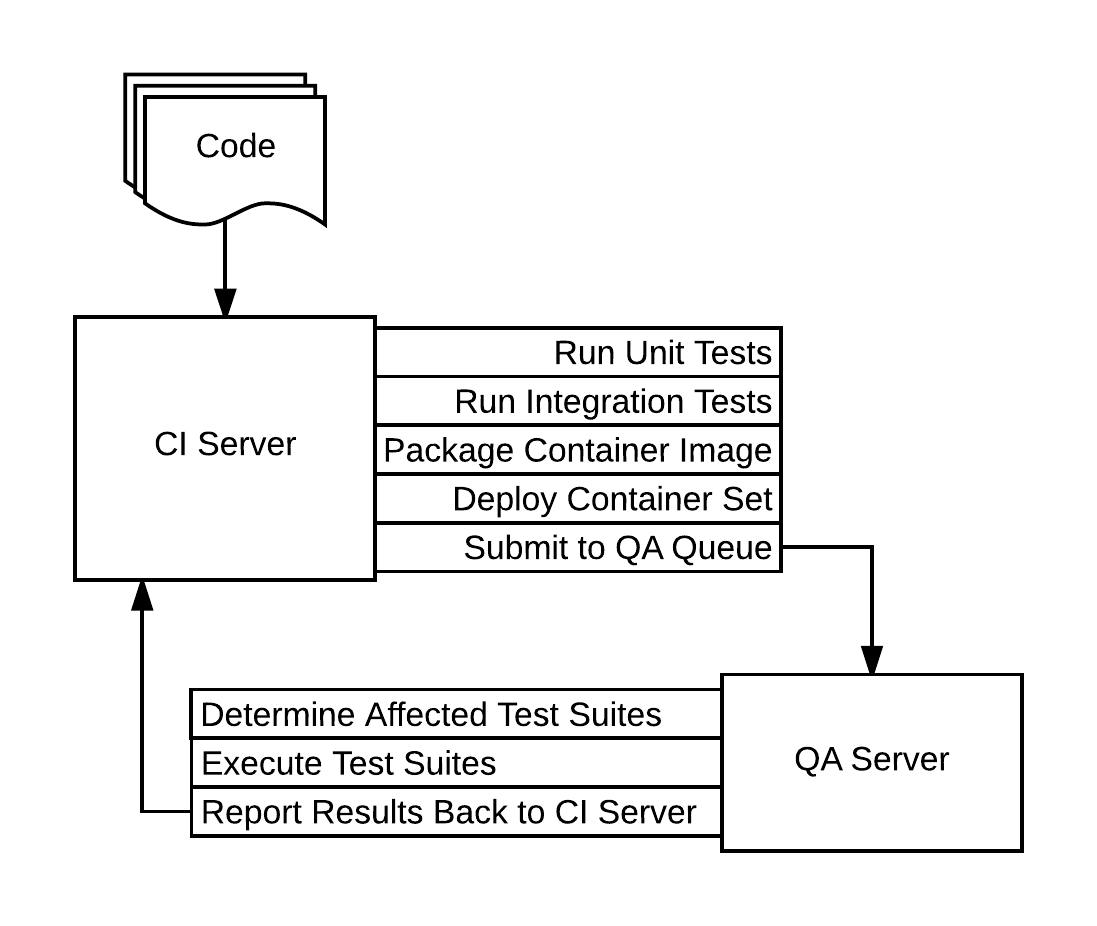

Warning: This image hides a lot of complexity

The above image is a rough outline of the steps I think would be necessary to have an extremely repeatable QA suite. The most interesting workflow step in the above diagram to me is the “Deploy Container Set” step, as it involves solving the problem of working out what needs to be deployed in order to completely test a feature. This includes picking up related branches for a given change, and deploying multiple consuming services such that they can be tested as well.

One of the other problems this solves is similar to the problems faced by devs sharing resources, in that it’s possible for others to affect your testing environment unexpectedly. By having as much of your testing pipeline isolated from others as possible you hopefully gain more confidence that your QA test suite will run to completion, and that any failures within the test suite are indicative of change either within the test suite or in the code under test.

The API

One of the things I had found frustrating with Docker was the poor GUIs. As much as I’m comfortable with the command line I find it hard to remember what options I need for some operations and understand at a glance what’s going on with all my containers.

How many containers do I have running of a particular type? How are they connected to each other?

Luckily, the docker engine can be set up to expose a RESTful API locally, though when doing this over TCP (such as when running Docker on Windows) this does come with some security considerations. This means that it’s possible to build a nice GUI that interacts with the docker API and can display any info you’d like, which could be very useful for knowing whether or not all your containers have spun up correctly, or displaying container information on some sort of wallboard.

🙈 🙉 🙊: gitlab $ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

653878baeb0d honours-project "nginx -g 'daemon off" 2 hours ago Up 8 seconds 443/tcp, 0.0.0.0:8080->80/tcp loving_dijkstra

🙈 🙉 🙊: gitlab $ curl --unix-socket /var/run/docker.sock http:/containers/json

[

{

"Id": "653878baeb0d2844a17de8699e6db6105e0ddb42f483d963ad01c0efea0fa214",

"Names": [

"/loving_dijkstra"

],

"Image": "honours-project",

"ImageID": "sha256:a39d168ab264b8aa8278dd2f7475ced977b1a35150b134e2348a84d754e91261",

"Command": "nginx -g 'daemon off;'",

"Created": 1472271794,

"Ports": [

{

"IP": "0.0.0.0",

"PrivatePort": 80,

"PublicPort": 8080,

"Type": "tcp"

},

{

"PrivatePort": 443,

"Type": "tcp"

}

],

"Labels": {},

"State": "running",

"Status": "Up 2 minutes",

"HostConfig": {

"NetworkMode": "default"

},

"NetworkSettings": {

"Networks": {

"bridge": {

"IPAMConfig": null,

"Links": null,

"Aliases": null,

"NetworkID": "b7b61a9ef18c58187101b8f2200284eca63e82e583e24926fc23731df7122cd0",

"EndpointID": "fa0ca43d385fe91f1f03c432084f3fd60c63d784f836447c6360b9ab3cab2930",

"Gateway": "172.17.0.1",

"IPAddress": "172.17.0.2",

"IPPrefixLen": 16,

"IPv6Gateway": "",

"GlobalIPv6Address": "",

"GlobalIPv6PrefixLen": 0,

"MacAddress": "02:42:ac:11:00:02"

}

}

},

"Mounts": []

}

]

As you can see this actually returns quite a lot of information, and on its own it isn’t really all that useful, though we can possibly alleviate that.

Next Time On Playing With Docker

Like I’ve said previously, when I’m trying to learn something new I’ve never come away from learning about a new piece of technology through reading blog posts and following tutorials with a real sense that I get it. It’s not until I try and do something where I’m not following a recipe set out by someone else that I feel like I begin building my own intuitive understanding of what’s going on. So I’m going to use this opportunity to learn about the Docker API and another piece of technology, which we will see in Part 2.

Subscribe via RSS